Reductionist Magic 6: General Spell Properties

Continuing on from my previous article on the soul models, it’s time to talk about spell properties. Whereas the second article in this series focused on properties of magic as a whole, this one will go into a bit more detail about common, general properties of different spells. What properties are these? How is their functioning limited by locality and by the general patterns we observe among the spells in the rulebooks? These questions, and the consequences of the answers to them, are what I’ll explore in this post.

As usual, if you are confused about any terms, make sure to check out the glossary, and if you are looking for other posts, check out the blog map.

When I talk about spell properties, I am talking about things independent of the actual effect of the spell - things such as range, navigation, targeting, propulsion, anchoring, and so on. Regardless of how a spell functions internally, it still needs to get to it’s target somehow - this means some navigation in space will be involved, and that navigation will have broad effects on spell function. For example, because of how Line of Effect works, we know that no matter what navigational method spells use to reach their targets, most of the time, it requires the spell to travel in a straight line. This should allow us to discuss spell properties without actually bothering with the lower-level details of actual spell structure.

So, what core properties can we distinguish in DnD spells?

Payload

This is the individual effect of the spell: anything that doesn’t fall into one of the other categories, essentially. For completeness, it has to be put somewhere, but there isn’t a lot you can say about it collectively. Discussion of spell payloads will be split into many different articles depending on spell type.

Pathfinding

If the spell is acting on some direct object, it has to get to it from your soul along some path. There are many algorithms that can implement pathfinding in spells, and here I will note their broad categories. Within this section, I assume that the spell already “knows” its start and target positions, so the only question is how to get from A to B.

Direct path. Not much to say here - spell flies from A to B, in a straight path. Simplest pathfinding possible, and does not require any external scans, but obviously vulnerable to even very minor obstacles. Example: Fireball.

Direct path, with minor obstacle avoidance. Same as the above, but the spell dodges minor obstacles in it’s path, trying to find holes in walls and such; anything moderately big stops it, however. Versatile, but the spell will need active detection capability to detect aforementioned obstacles and go around them. Examples: most spells requiring Line of Effect.

Non-direct simple geometric path. Spell flies along some relatively simple, predetermined non-linear path (e.g. a semicircle), dodging minor obstacles. Example: none off the top of my head; but I see no logical reason why this would be impossible. This pathfinding method should allow spells to be fired around corners.

General path finding. Spell attempts to find any unobstructed path to the target, within some limits, even if it’s not direct or not known in advance. Because the spell first has to find the path to the target, it logically has to be split into two parts: first, the environment is scanned through some method and a path is found. Second, the active component of the spell follows this path to the target. Because of this, the spell obviously has to contain a significant scanning component.

General pathfinding, with plane hops. Same as the above, but hopping between planes is allowed during the pathfinding stage. Examples: Teleport, Plane Shift, Scrying.

Multi-stage navigation. Any spells which use different navigation methods at different stages. For example, Aggressive Thundercloud uses a simple path with obstacle avoidance when it is initially cast and manifests at the target location, but does not have obstacle avoidance when it is later directed.

Propulsion

Pathfinding deals with how to find a path to the target; propulsion deals with how the spell follows that path, or otherwise moves through the environment. I see several ways this can be achieved:

Spell has no propulsion of any kind: it’s created by your soul, and does not move away from it. To deliver it, you will most likely need to touch someone. Alternatively, spell can be attached to some object, and delivered by it. Example: Touch of Fatigue.

Spell flies to the target by inertia: it has weight and most likely obeys gravity. Example: Produce Flame.

Spell extends itself towards the target, until it touches them and delivers the effect. Examples: ray spells, Ghost Whip.

Spell flies to the target at a set speed. Some spells have some kind of set maximum speed at which they operate, and use that for navigation. Example: Aggressive Thundercloud.

Here it is important to note how such a set speed may arise. See below for a note on relativity.

Spell flies to the target at “spell speed”. Most targeted spells move towards the target quickly enough that they can’t be effectively dodged or avoided. Rules do not state at which speed they move, but we can reasonably assume it is at least as fast as arrows shot from a bow - another thing that likewise can’t be deliberately avoided (mythbusters have shown that you can kind of catch arrows in episode 109, but it’s on the very edge of human ability in specific circumstances). This means we can put a lower bound on spell speed of about 100 meters per second. I don’t see any way to derive a higher bound to spell speed, other than the obvious limitation of the speed of light. Examples: most spells.

Key difference between set speed and spell speed is that the latter is large enough to not be a practical factor in tactical considerations. Imagine a rocket that flies around at three times the speed of sound. Now, it could be three times or seven times, that speed can stay constant during flight or it can vary, but when you are concerned with tactical fighting inside of buildings, this rocket arrives at its destination effectively instantly.

Here a question may arise regarding spell speed and counterspelling. Because a counterspell has to touch the enemy spell, would the speed at which the spells move affect your ability to do so? I don’t think this is a practical consideration: spells are assumed to take some time to cast, somewhere on the order of rounds, because you can typically only cast 1 spell per round. A round in DnD is assumed to be about 6 seconds long. Therefore if we assume you cast your counterspell half a second faster than the source spell - very reasonable compared to 6 seconds - your counterspell will have at least 50 meters of lead - more than enough to cover most common spell ranges.

Speed of light has to be an upper bound on spell speed because anything that lets you travel faster than light can be used to travel backwards in time, which we have defined as impossible in the second article of this series.

Extradimensional travel. Some spells (Most notably Plane Shift, but also some others) have to involve some travel through the planar boundaries in order to work. This will be further explored when talking about plane travel in general.

Multi-stage spells. These are spells that have separate stages with separate propulsion methods. For example, Fire Seeds are touch-ranged initially (when the acorns are transformed), and inertia-based later (when the physical acorns are thrown). Obviously, once you understand the individual limitations of each stage, you will understand the limitations of the multi-stage spells as well.

Note on relativity

Physics since about the time of Newton has been founded on ideas of relativity. In popular consciousness this idea is associated with Einstein, but it is much older than that. Newton’s original relativity said that there can’t be a privileged frame from which to measure velocities: you can only define velocity of an object, or of a coordinate frame, relative to another object or a frame: but there is no such thing as “objective” velocity. Einstein expanded it to include relative accelerations, and the fact that speed of light is constant in all frames.

This idea is pretty fundamental. All physical laws are defined in this way. Not only the laws themselves, but even the basic ideas of geometric symmetry don’t really make sense if there is a privileged frame of measurement. This is of course a big problem for our purposes, because a whole lot of spells seem to be based on absolutist foundations: they say that some spell effects can’t move or have a set speed at which their primary effect functions. But if something can’t move in one frame, it has to move in a different frame; and if something has speed V in frame A, then it would have speed V + V2 in frame B which is moving with speed V2 relative to A.

How do we reconcile these two mutually incompatible ideas?

Let’s start by figuring out what is being used as the other side of the velocity measurement: there has to be something in relation to which our velocities are being defined. Here I see three logical options:

In relation to some local physical objects: e.g. ground or air.

In relation to local spell-like objects: e.g. some kind of local “mana field”.

In relation to some distant physical or spell-like objects.

I will call the object(s) relative to which the velocity of the spells is measured “anchors”.

To give some real life examples here, imagine that we hammered a giant metal spike 50 meters long into the ground: for all intents and purposes, that spike isn’t going anywhere, it is immobile. However, that immobility is defined in relation to the ground: in relation to the sun this spike is moving. Likewise, if we moved all the local ground somewhere (e.g. with an enormous landslide), it would move relative to the earth. This is our option 1. Option 2 is the same, but in relation to some large local magical object, such as a different spell.

Option 3 might raise some eyebrows: doesn’t it violate our locality assumptions? Well yes, but actually no. For example, imagine that we were living on top of a hundred floor skyscraper, and had an immobile table to play billiards, bolted to the floor. In principle, this table is only static relative to the 100th floor of the building; but because the skyscraper is very solid, we can also say it’s static relative to the earth as a whole. As we can see, even though stability is enforced entirely by local forces, we can sensibly talk about it on a global level while abstracting away the connections in between.

Now that we have converted our velocities to a local definition, how can spells be static relative to the anchor? Well, in accordance with first Newton’s law, we need a force that is going to compensate for any other forces acting on our spell: for example, if someone pushes on a force wall, there has to be an equal force keeping the force wall in place. How this force is generated isn’t important. What is important is wherever this force obeys Newton’s third law.

Here we have two options:

Corrective force does obey the law: an equal and opposite force acts on the anchor.

Corrective force doesn’t obey the law: forces acting on the spell don’t act on the anchor.

In either case, if an anchor is moved relative to a third object, corrective force acts on the spell to keep it static relative to the anchor. Some trivial reflection on forces in various inertial and non-inertial frames easily shows this is the only possibility: there is no internally consistent situation where, for example, we can move the anchor while keeping the wall in place, but not move the wall while the anchor is in place.

I would highly advise any designer of magical physics to use the first option here. Violating Newton’s third law inevitably violates Newton’s second law, conservation of energy, and the rest of physics very quickly: see the argument here. If you must keep the anchor isolated, then I strongly suggest you use a second anchor: one to determine the position the spell should be in, and another to offset the forces. Otherwise, you may find that your spells lead to very strange consequences: see this post for an example of a force wall levitation engine you can build based on a violation of third Newton’s law. I will do my best to stick to the first kind, until and unless some overly specific spell forces me to do otherwise.

Now for the question of spells that have a set speed relative to their anchor. Intuitively, I think about maximum speed being determined by two different mechanisms - the “bicycle” one and the “airplane” one.

Imagine that you have two forces acting on your spell: one is “propulsion” and the other is “drag”. Propulsion tries to make the spell go faster, while drag tries to make the spell go slower. Both of these forces may depend on speed relative to the anchor, and the maximum speed for the spell is determined when they become equal. At lower speeds, propulsion is higher than drag, because otherwise the spell won’t move at all. At higher speeds, the drag is larger. How sharply the drag raises determines wherever maximum speed is a soft or a hard cap.

Bicycle mechanism refers to a situation where the primary reason why propulsion dips below drag is that propulsion efficiency decreases with increased speed. When riding a bicycle, to increase your speed, you have to move your legs faster and faster. But there is a certain effective speed at which you can move your legs, and trying to go faster decreases your efficiency: this determines your max speed. This is why bicycles have gear shifts: with a lower gear ratio, you can move your legs slower, go back to peak leg moving efficiency, and thus move faster. Airplane mechanism refers to the opposite situation: drag increases sharply with speed, just like air drag for airplanes.

Which of the mechanisms makes more sense would depend on specifics of each individual spell. To summarize, spells become “unmovable” because they are linked to some large practically unmovable anchor, and spells have a set maximum speed due to propulsion and drag interactions relative to their anchor.

Scanning & communication

In order for spells to function, they require a large amount of information - regarding environment, their targets, position of the caster, and so on and so forth. The process of collecting this information is what I call “scanning”. Likewise, some spells have to communicate with the caster - for sensors, this may involve sending back information, while for “directed” spells (e.g. flaming sphere) caster would be sending instructions on where to go next. With some reflection, it becomes clear that these are actually the same problem - transmitting and receiving information.

In the case of communication, the caster and the spell take on the roles of transmitter and receiver. In the case of scanning, we have either passive scanning (the spell acts as the receiver of information and the environment acts as the transmitter) or active scanning (the spell acts as a transmitter in order to get the environment to act as a transmitter). I’ll therefore talk about information transfer in general, instead of about the specifics of these two types of it.

Before we do that though, it seems prudent to introduce two new concepts. In classic DnD, there is Line of Effect, which determines wherever certain spells could be cast on the target. As I’ve mentioned previously, Line of Effect is simply a natural consequence of how impermeability of solid objects to traveling spells and spell pathing interacts. Of course, I’ve already mentioned different pathfinding and propulsion methods, which should logically lead to different “line of effect” type interactions. We can therefore define a set of continuous paths between two points, such that a spell following along those paths wouldn’t run into any impassable objects or spells. I will call these paths “Path of Effect”. Line of Effect is then simply any Path of Effect that is sufficiently straight.

Of course, we can go further. Flickering Path of Effect is like Path of Effect, but the path does not have to be continuous at any one point in time - it just has to be continuous when taken over a certain time window.

For example, imagine a room made out of force walls, and split into three sections by two additional walls. At time T = 1 minute wall C turns off. At time T = 2 minutes it turns back on. At time T = 3 minutes wall D turns off.

At no point is there any Path of Effect between points A and B. But there is a Flickering Path of Effect - a spell could have, in principle, waited in the “airlock” and gotten through.

With this in mind, I see three primary ways to exchange information between the caster and their spell.

Extended spell. The easiest way to transmit information is to use a wire. Here, the spell takes the place of the wire. When communicating information, caster keeps one end of the spell attached to their soul, and the other end of the spell contains the active element of the spell. When scanning, the other end is used to poke at the environment like a stick for the blind, using spell’s properties to detect walls and other interesting features.

Packets. Instead of using a wire, we can use small microspells as packets of information, shuttling back and forth between the caster and the controlled spell, or the caster and the scanned environment. This changes the way the control works pretty radically: for example, it seems harder to subvert a control over a directed spell using an extended spell, compared to the packet system where you can do a Mage in the Middle attack. On the other hand, extended spell presents a huge target for dispelling; furthermore, it requires Path of Effect, while packets could make do with just Flickering Path of Effect.

Note: existence of a Mage in the Middle attack is, best as I know, purely theoretical, based on my reasoning around how controllable spells can work. As far as I know, there are no abilities that give you control over the spells of other people.

Packets is my model for scanning divination spells, where I call them microspells.

Real light & sound. Finally, any method of transferring information using real world physics should work too: light of all forms, sound, and so on. Spells can detect these, emit them to function as an active scanner, and use them to communicate with the caster. Using this method for communication makes spells secure against some forms of tampering and weak towards others, such as illusory magics which modify light or sound. The primary benefit, in my mind, is not requiring any Path of Effect and potentially hiding the fact that communication is taking place in the noise of the real world.

Here one could ask if there could exist some way to use magical light and sound - some kind of “magical photons” that could be used for communication. In my opinion postulating the existence of such particles is unnecessary. I think that a theory of magic can be established without introducing them, and everything they would entail. However, should they become necessary, then technically I have already included them. After all, photons are just packets of information that travel in straight lines, and so would fall under the second method of information transfer. The main difference would be in postulating the existence of some process that generates these magical photons passively.

Range

Most spells have a certain maximum range. How could this property arise as a consequence of the things I have discussed above? I see several possibilities:

Spell length. As I described in the Communication and Propulsion sections, some spells will stretch all the way to their target. It therefore stands to reason that if there is a maximum reasonable range to which the spell can stretch, that would be the maximum range of the spell. Removing this limit without modifying the spell itself would be difficult.

Memory and processing limitations. Complexity of pathfinding increases sharply with increase in the land area the spell may have to pathfind over. If there is a certain maximum complexity that can be handled by the pathfinding algorithm, that can determine the maximum effective range of the spell. Likewise for scanning - the larger the area to scan and analyse, the more difficult it would be. Off the top of my head, I think only something like Locate Object would be appropriate for this kind of limitation. Modifying this range would thus involve finding a way to process more information, or to do it more efficiently.

Spell life. Certain spells may effectively have a “timer” built into them - either designed or inherent to their structure. When this “timer” expires, the spell falls apart. If the movement speed of the spell is known, such a timer would then determine the maximum range of the spell.

Power drain. Some spells have to be continually sustained by a constant expenditure of magic power. Once this power runs out, the spell ends. Modifying such a range limit would involve stuffing more power into the spell - which may be a natural consequence of increasing in level, or it may be impossible due to strict design limitations.

Propulsion. Similar to the previous category, with the main difference being that the spell doesn’t end, it just stops moving, sans inertia. In my view, this is the most appropriate range limitation for homing combat spells. There can be two ways to modify this range limit - either make the spell more propulsive, or add additional movement to the spell not based on regular spell propulsion, for example by moving the surrounding medium.

Spell damage. Some spells are inherently unstable, and collapse over time. Maximum range is thus determined by how long the spell can stay together. From the outside, the only way to distinguish this from a power drain range limit would be if the damage depended on the environment.

Targeting. Targeted spells may have an effective range at which they are effective, simply based on your ability to aim them (e.g. Produce Flame). Think about it like aiming a gun: sure, it could shoot for hundreds of meters, but you probably can only effectively aim it in the first 50 or so. Attempting to use spells beyond this range would lead to so many misses that it would be pointless to try. Should you find a way to more effectively target such spells, their effective range can be easily extended, until they run into one of the other limits.

Anchor

Spells that act over a long period of time have to define the location of their effect somehow. While for some spells (e.g. Aggressive Thundercloud) this is simply the same location as where they were cast, for other spells this doesn’t really work. For example, creature buffs have to act on the same person throughout their duration regardless of how they move around. This is what I refer to as an “anchor” - the spell is anchored to something, and determines its position, and thus continuous target of its effect in relation to that. For static spells or spells with a set speed this can be the same object as that which sets the speed, or a different one - e.g. in my view flight spells should be anchored to the air for speed, but to the creature for determining where the spell is acting. Here are the main ways I can see the anchoring working:

Inertia. Aggressive Thundercloud case - spell has a certain inertia to it, and keeps acting on the area simply because that’s where it’s located. Key thing about this type is that if the spell itself doesn’t move, or isn’t moved by something, it will simply remain in place.

Location. Spells like Black Tentacles - they are tied to the ground in the area, and so will move with that ground (e.g. if they are cast on a ship). See also my note on relativity regarding static spells.

Object/Body. Similar to a spell tied to a location, these spells are tied to a specific object, or (often) to the body of a creature. Naturally, because of this, they would move with the body or object; furthermore, if the soul controlling the body leaves, it will no longer be affected by these spells. Spells such as Summon Monster are a notable special case in this category: for them, spell creates its own anchor.

Soul. Instead of the body, the spell is tied to the soul. This means that it will stay attached to the soul regardless of where the soul goes, even if that soul is making multiple possession jumps. A good example of such a spell would be Geas. Deciding whether a personal buff spell is tied to the body or the soul resolves the question of how that buff would behave when subjected to spells like Magic Jar, Possession, Astral Projection and so on.

Second spell. A fairly rare case, but instead of being tied to a soul the spell is tied to a different spell. The only case I can think off the top of my head is Contingency. Obviously, the second spell (one triggered by contingency) would follow the contingency link.

Target selection

Spells have targets. This section deals with how spells determine which targets those are.

First hit. Simplest target selection mechanism - spell acts on the first person, or thing, hit. For touch spells, this is first person touched. These spells are indiscriminate: this means if your aim is off, and the spell doesn’t home in on the target, it can hit unintended targets. Main benefit of this targeting system is that it requires minimal information. Example: ray spells.

Activation at a target point. Spell doesn’t do anything until it reaches the target point in space, where it activates. Key difference from the First Hit targeting system is that if the spell is prevented from reaching the target point, it likely will not do anything. Furthermore, the spell can’t “overshoot” it’s target. Benefit is that this is a fairly precise way to place spells, and allows spells to use better pathfinding methods. Drawback is that this requires the spell to determine the target position somehow, relative to its starting point or to other objects, and relative to its current position. Example: most summoning spells act this way.

Target specific object. Spell selects a specific object or creature, and will attempt to target them specifically, assuming it can get to them, ignoring everything else. This means it will most likely have homing capabilities built in, though this isn’t strictly speaking necessary. Because of this single-mindedness, if it’s prevented from acting on the target, it will do absolutely nothing. Of course, this requires the spell to have some consistent way to determine the position of the target object, all throughout the navigation phase. This is fundamentally a scanning problem, and so will suffer all the same limitations. Example: Baleful Polymorph.

Two questions arise in relation to this targeting method. First of all, I have previously mentioned that spells have to be local to where the effect is produced, and furthermore that they can’t go through solid objects. Then how do spells affect the insides of solid objects? I will answer this question later down the page. Secondly, how do spells select an object to be affected? What is an “object” anyways? This question, on the other hand, has its own separate post.

Spacial selection. Instead of selecting a specific object, spell affects everything within a certain well-defined area. For example, Transmute Rock to Mud works on the basis of 10 foot cubes. Defining such an area is both a scanning and a pathfinding problem: all the points of the spell defining the border of the affected area have to first locate their target positions, and then find their way there.

Here it’s obvious that there are a myriad of distinct ways of making this process work, but some stand out as the most logical options. I discuss them in a later section.

Combined targeting mechanism. For example Fireball explodes at target point, unless it hits something before then.

Permeability of objects

Objects have different permeability to different spells. For example, Transmute Rock to Mud can go 10 foot deep into a stone wall. Divination spells like Detect Magic or Detect Secret Doors have a classic permeability of “The spell can penetrate barriers, but 1 foot of stone, 1 inch of common metal, a thin sheet of lead, or 3 feet of wood or dirt blocks it”. On the other hand, when it comes to Line of Effect, solid objects are almost completely opaque to spells - even a sheet of paper can block them. It is obvious that the questions of object permeability differ not only from one spell to another, but also from one stage of the spell to another - for example, Transmute Rock to Mud is bounded by the regular line of effect rules during the pathing stage, but can extend its effect deep into the rock during the actual effect stage.

Overall, I see several ways to treat object permeability:

Like a scanning divination spell: use either absorption or density method of measuring penetration, like scanning divination spells. This would make the effect of the spells heavily dependent on the environment, and probably unsuited to underwater environments.

Like Line of Effect: “solid” objects are completely impermeable to spells. This would make spells usable in water, but blockable by dense grass, paper, clothing, and so on.

No limits on permeability aside from spell length: spell freely goes through solid objects and affects them. E.g. the effect of Transmute Rock to Mud works like this. This is mostly limited to the actual spell effects.

Filtered or combined permeability: this functions like one of the above types combined with another, or filtered in some way: for example, fire spells consider water to be solid, but not water vapor, which means they have to filter based on the density of water molecules in the local environment in addition to the regular line of effect rules, with a very low penetration depth for water densities appropriate for liquid water.

Logical simple spatial selection algorithms

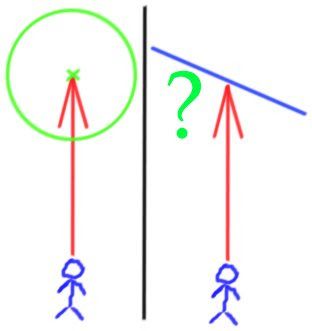

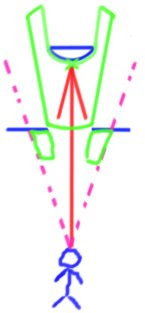

Left: Caster (blue) casting a spell that targets an area (green) by targeting a specific point with line of effect (red). Right: caster attempting to cast the same spell at a spot where the target area can’t fit due to a wall. Resulting spell area is indeterminate.

Spatial selection (selection of a section of space to be affected by a spell) is a complicated topic, and there are infinitely many ways for different spells to implement it. Nonetheless, some methods seem like natural choices due to their simplicity. I will outline them in this section, alongside the consequences of the spell using these spatial selection methods.

Out of the seven methods I note here, DnD rules include two: spreads and emanations, as well as bursts which are equivalent to emanations but don’t persist over time (e.g. Magic Circle against Evil is emanation, while Fireball is a burst because area effect is gone immediately after the explosion). It’s thus valid to ask why it’s necessary to discuss this topic in more depth. The problem, however, is that the core rules do not apply these methods to all Area of Effect spells: for example, the spatial selection method of Create Pit is indeterminate. Furthermore, some spells have an effect which takes up a significant amount of space, but aren’t considered Area of Effect spells: for example, Gate makes a massive portal in space, but rules regarding how that portal expands are indeterminate. It’s obvious to me that there needs to be a single list of spatial selection methods that would be used for all spells with any areas of effect unless stated otherwise.

Obviously, individual spells can have their own, more complicated spatial selection methods. Furthermore, all of these methods only differ between one another only when the spell fails to expand to its full area: it is then logical that the spell failing entirely would also be an option. This is, effectively, an “eighth method”. DnD rules note something similar, under Spell Failure in the magic chapter: “If you ever try to cast a spell in conditions where the characteristics of the spell cannot be made to conform, the casting fails and the spell is wasted”. However, what exactly “characteristics cannot be made to conform” means is extremely unclear; furthermore, I personally would not like a situation where spells with reasonable effects (e.g. Create Pit) would fail entirely when cast in a room even 5% too small.

Expansion from the target point

Simplest method is to simply expand the boundary of the spell from the target point until it hits a solid object, and then stop. This method is used for the emanation or burst spells in the rules. This is most appropriate for spells where spell effect is the same at every point in the area, and can also represent things like explosions.

Expansion from the target point while preserving shape

Spell shape is preserved during expansion: therefore, if the spell can’t go through a wall, expansion stops. Most appropriate for spells where the shape of the area is important. Note that the target point may not be the geometric center of the spell, and can instead be a point on the boundary or somewhere else in the spell area.

Expansion from a movable target point while preserving shape

Similar to the previous method, but the spell doesn’t attempt to keep any target point stuck in space. If it can’t expand in one direction, it expands in another, until it’s completely blocked by the surrounding objects or reaches target size. Likewise appropriate for spells where shape is important. Do note that the spell can be pushed by the expansion in unpredictable directions, and the caster would be aware of this.

Expansion with a spread algorithm

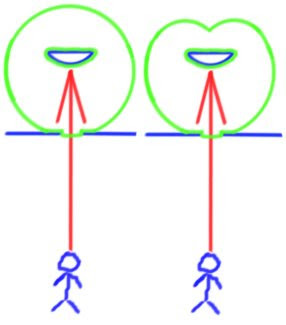

This is the method used by the spread spells in the core rules. Instead of the spell being constrained by the shape, it spreads out from the target point, and affects either everything within a certain distance of the target point (left), or everything where the shortest unobstructed path to the target point is below a certain limit (right). Notable feature of this algorithm is that it can reach around corners, and create holes within the spell area.

Volume-preserving expansion

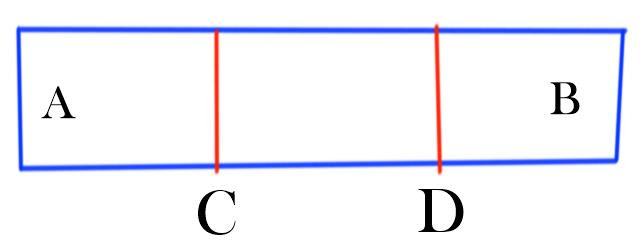

Spell being cast within a confined space that uses spatial selection algorithm 1 (left) and a volume preserving algorithm (right)

Similarly to one of the aforementioned algorithms, the spell spreads out from the target point, but in this case it preserves the volume affected by the spell. This means that the spell can affect a much larger effective area if cast within a confined space. This can have wildly unpredictable effects because humans don’t have a good intuition for how confined certain spaces are in terms of volume.

Let’s say that we have a spell with a spherical area of effect that is 6 meters (~18 feet) in radius. This is a fairly large area, but not ridiculously so. However, if cast on the ground level, this radius becomes 25% larger because the actual spell area is a hemisphere as opposed to a sphere. If cast on the ground next to a wall, it is 59% larger (9.5 meters instead of 6). Similar expansion is present when casting in a room with a 3 meter high ceiling. However, all bets are off when it is used within a corridor with a 3 by 3 meter cross section: this spell affects a full 100 meters of that corridor. If the cross section is merely 2 by 2 meters (tall person being ~1.8 meters, this is realistic), this becomes 226 meters. As such, all kinds of intuitions regarding how far away you have to be to be “safe” become wildly wrong, by more than an order of magnitude, when the spell is used even in fairly normal situations. This effect becomes more pronounced the larger the initial radius of the spell, because volume scales as a cube of the radius. Keeping this in mind is important.

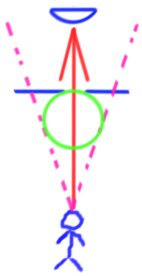

Expansion during flight while preserving shape

Of course, there is no particular reason why the spell has to expand after reaching the target point - it can also expand during the path there. This would imply that the degree to which the spell can pass through gaps will be determined by where those gaps are, and the interplay between the force directing the spell to the target point and the force making the spell expand.

Expansion during flight without preserving shape

If we apply the algorithm 1 for spell expansion to the flight stage, we will get a result drawn above. Intuitively, this can be seen as “firing” the spell like a bunch of pellets from a shotgun, with some pellets not reaching their target point. Here, the parts of the spell blocked before reaching the target area may be gone, or may end up being their own separate spell chunks, depending on how the spell expansion works. If they do end up as their own spell chunks, then the spell will have multiple unconnected spell areas: this is important to keep in mind.

I think this concludes my overview of the various general properties of spells. Overall, I feel that it’s much less prescriptivist than the previous posts in this series. Instead of describing how magic should work, it mostly just lists out the ways it may work. However, I would actively use this post as reference material for future posts, when I will talk about magical effects themselves (e.g. transfiguration, teleportation, healing); and about individual famous DnD spells. Furthermore, I think narrowing down the space of possibilities from everything imaginable to only a handful of choices should be helpful for everyone.

Meanwhile, if you enjoy what I write, you can subscribe to receive updates by email:

Licenses:

Title card uses "Magic Circle" by AnimeStuff_Make (licensed under CC BY 4.0) and "Fireball" by The Wandering Angel (licensed under CC BY 2.0) and as such is licensed under CC BY 4.0 itself.