Reductionist Magic 2: Magic fundamentals

Previously I announced a pretty ambitious project: applying reductionism to DnD magic in order to establish broad “laws of physics” that could be used to consistently model circumstances that aren’t defined in the rules. Today I’ll establish some fundamentals for this project.

As usual, if you are confused about any terms, make sure to check out the glossary, and if you are looking for other posts, check out the blog map.

Let’s start with specifying what this Theory of Magic will be about. First of all, I will only be breaking down DnD magic. I believe that a lot of the resulting laws will be broadly applicable between magic systems - after all, broad classes of effects are often fairly similar - but at the end of the day, I have to focus on something specific.

Because DnD has multiple different versions, I have to further specify I will be analyzing Pathfinder 1st edition, with additions of Path of War and Psionics from Dreamscarred Press. I suspect these additions will not be terribly relevant, but if they are, then there is that.

Furthermore, this will be a magical theory from the perspective of the GM. It will say nothing about what the occupants of the world know about magic. It will also say nothing - or, rather, not much - about how magic is experienced by the practitioners of it. Both of those factors are, in my view, independent from how GM should behave when asked about interactions of magic with something unusual. Occupants of the world can know less than you do - or be implied to know more than you do, using a dozen different methods GMs have access to.

Likewise, I will say nothing about what your players know out of character. This theory is here to help you describe what happens in the world. Your players knowing it can be beneficial, especially when it comes to complex planning, but it can also be a large drawback. Knowing a lot about how magic works on a fundamental level may make your players more willing to push the boundaries of magic, and thus likely to reveal inevitable inconsistencies in it. As I’ve mentioned previously, this is not going to be a fully consistent theory of magic - creating that would be too much effort. Therefore, if you push on it sufficiently, holes will start to show up. Wherever you want that to happen as a result of player action is a decision I can’t make for you.

Next, our magical theory will almost certainly have not just hidden inconsistencies, but straight up holes - obvious, large effects it can’t explain at all. This may happen with the biggest magical effects - the kind campaign is built around, or even with some commonly used spells with particularly unusual effects. This is fine, because the point isn’t to explain everything, just to significantly increase our explanatory power. If you want a single spell that won’t fit these laws, well, then I guess it won’t fit them.

Lastly, I will try to keep the magic laws as general as possible. There are two reasons for this: first of all, adherence to Occam’s Razor when it comes to explaining known magical effects (i.e. defined effects of spells in the core rulebook). Second, I’d like to keep the laws open enough that they are easy to adapt to any homebrew setting other people may be using.

Now that this is out of the way, let’s start our scientific investigation of magic. We have our experimental data - all the rules described in the books, as well as vague images of the setting we’d like to develop. We have our already known laws of physics - we’d like to preserve them if at all possible, to rely on their high degree of consistency. And we have our intuitions of simplicity. All we have to do is the same thing as any other scientist in the 19th century - figure out some new laws from this.

There are two big ways in which our work differs from real scientists, however. First of all, we won’t be able to perform experiments, because it’s all in our heads. This means we won’t have any real way to cross-check our theories. Secondly, we can freely modify the physics themselves - after all, that’s pretty much our job here. This means that we will have, effectively, a reverse scientific method - instead of coming up with the simplest law to explain the effects occurring in nature, we will come up with the simplest law to generate those same effects, one that also ensures we minimize undefined behaviors. If as a result we’ll have to modify some spells - effectively, modify our experimental data - this would be fine, as long as it’s not too much.

Enough talk, let’s start defining laws.

There is no way to travel backwards in time.

Why? Time travel is an immense headache to make consistent. All sorts of problems you can assume to be impossible to solve normally become trivial with time travel in the picture. With some relatively simple tricks, and a time loop, you can achieve an effectively unlimited amount of computational power. You, the GM, do not have an effectively unlimited amount of computational power. It’s a really bad idea to give players tools they can use to solve mathematical problems you can’t even properly think about. Even aside from that kind of abuse, simple problems like “what if players get into the same room as themselves” will make you reach for a noose. Add on top of that the fact that NPCs can do this too, and could do it since the world existed as it currently does, and I hope it becomes clear why it’s better to have this simple law in place.

What does this change? Only a few individual spells, to the best of my knowledge, which would have to be removed. However, effects on your sanity are truly unmatched.

Spells are made out of three-dimensional objects made out of spell-matter. Spells have positions in real space. Interactions between spell matter and other spell matter, or between spell matter and regular matter, are for now undefined. Even the identity of it is undefined - it may or may not be regular matter, but it is something, and for now spell-matter is the term I will use.

Why? There are many ways to define spells on a physical level. However, the simplest and the most consistent one, in my opinion, is to treat spells like objects. This lets us think about various things spells do - like travel from place to place, interact with other spells, creatures or the environment, and so on - as interactions between three-dimensional objects. Physics has a very robust language for talking about 3D movement, and I think borrowing that language will be of great benefit.

What does this change? Directly, not much, but it has massive implications on how many other spells have to work. Also see laws 3 and 4.

Spells can be created by a known set of natural circumstances, by souls, by magical items or by other spells. In all of these cases, the new spell is always created in the immediate area of the circumstance, soul, magic item or originator spell. Spells are destroyed when they expire (in case of spells with “instantaneous” effects, such as fireball, when the effect fully concludes) or when they are dispelled.

Why? If you have distinct objects, those objects have to come from somewhere and end up somewhere. This gives us a strict set of situations when spells are created and destroyed: nothing else works. If you don’t have a soul, a magic item, a different spell, or are lucky enough to fall under circumstance rules, you can’t do spellcasting.

What are “natural circumstances”? A term for any kind of “natural” magic, produced by nobody, if such exists in your setting. Wild Magic, unusual area magical effects, all of that goes here.

What does this change? Best as I know, nothing. This just puts this explicit limitation down on paper.

In order for a spell to affect the physical world, or another spell, or a creature, at least one part of the spell has to be in the immediate area of the effect produced.

Why? To eliminate action at a distance. Locality is a very, very strong principle in physics. Every single physical law - with the possible exception of some quantum effects - is local. This means that what happens at point A depends only on what is at point A, or at points immediately surrounding it. The only way something can affect something else at a distance is to transmit this affect through all the points in between. Preserving this principle is absolutely essential, in my view, in order to keep various fundamental assumptions of physics consistent.

What does this explain? Now, with a combination of laws 2, 3 and 4, we can finally have our first proper explanations for what is going on in DnD magic. Strap in.

Line of Effect. Line of effect is a concept relating to the targeting of spells. Essentially, in order to target most spells, you have to have a clear line between caster and their target. If it is interrupted by a solid object, then the spell can’t be cast. Using our interpretation of what the spells are, line of effect is simply a statement that most spells move directly towards their targets and can’t go through solid objects. We even get a measurement of the size of the spells: line of effect ignores any object with a hole at least a foot across, so diameter of the spells is clearly about a foot.

However, what is not stated in the rules is how do other spells - without line of effect requirements - reach their targets, for example Scrying. We don’t (as of yet) define targeting for spells. But what we can say is that a spell needs to have at least one unobstructed path to reach their target, be it through the air, or by bypassing planar boundaries (more on this later). This means that if there is no such path and the target location is under Dimensional Lock, spells, and Scrying in particular, would not be able to reach their target. This is simply a natural consequence of how we define spell movement.

Similarly, if you are in a dimensionally locked location and surrounded by force walls (which stop all spells from going through), you can’t scry anywhere outside of your prison.

Because of locality, the caster can’t know for certain whether they have a free Line of Effect to some target until they either cast a spell at that target, absorb some kind of “magic photon” emitted by it, or emit some kind of active “ping” to check that the path is clear - ping that would be detectable in principle. We can, generally, dismiss the existence of magic photons that would let casters see wherever they have line of effect passively, due to among other things implications on divination spells - more on that in a later post. Therefore, logically, if a spell is cast and ends up not having line of effect, it would either take effect on whatever it hits first, or be wasted. This means that if you are trying to minimize the chances of detection, and the enemy has an invisible screen between you and them, you will waste your first shot.

As a corollary, there should exist a cantrip, available to all classes, that would allow you to check wherever you have Line of Effect to a specific point, simply as a point of convenience.

Detectability & steerability of spells. The only way for a spell to be detectable - for example with Detect Magic or Arcane Sight - is if the detector interacts with the spell in some way, or with some “radiation” being emitted by it. This works as normal for most spells, but a key difference appears when we consider spells whose actions can be “steered” while they are in progress, such as Flaming Sphere. Because we are avoiding action at a distance, the only way for such a spell to receive new information from the caster is to have a direct link to them. This must take the form of the spell stretching a line all the way back to the caster, or of some form of “packets” of information being sent back and forth, or (unconventionally) the spell using physical mediums to exchange information, such as sound or light. If the medium is magical, however, we would expect the active link between the spell and the caster to be visible to the same extent that spells are normally visible.

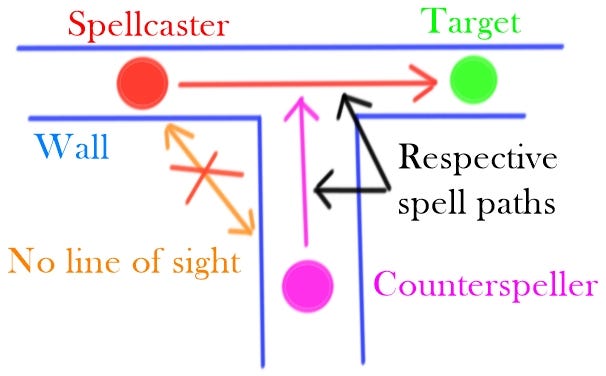

Counterspelling. Counterspelling requires two casters: one to cast the original spell, and another to counterspell it. Conventionally, this requires seeing the other caster, in order to identify the spell being cast. However, with our definition of spells, we can see this isn’t strictly necessary. What has to happen is for the counterspelling spell to come into contact with the original, and this can happen in a variety of circumstances. For example, counterspell should be possible in the picture below, assuming the spell to be cast is known in advance.

Laws 2, 3 and 4 collectively formalize the intuitions about spell movement and positioning that are pretty clearly present in the core rules.

Souls exist. Souls are, like spells, three-dimensional objects that most living creatures have. There is a loose 1-1 mapping between the location of the body and the location of the soul, such that if you touch the hand of another person, your souls can be considered in contact too. To cast spells, you need a soul (see previous laws for exceptions), in which case cast spells will arise in contact with your soul. Souls contain the majority of the mental processing of the creature’s mind, and control the body’s actions via a soul-body link. Bodies without souls are effectively comatose. When your body dies the soul becomes separated from it, and may be forced to depart into the afterlife.

Why? DnD rules have obvious references to souls in a lot of places, like undead creation rules, various resurrection spells, or the soul jar spell. Unfortunately, the rules for how souls behave are typically determined per spell. These are somewhat consistent, but not entirely. Putting them all in one convenient place only makes sense.

What questions can we now easily answer that we couldn’t before? Well, how about some of these:

Line of Effect says that a barrier with a foot-wide hole isn’t considered a barrier for the purposes of spells. What about two such barriers one after another? Imagine a wall with 1 foot holes every 5 feet. For spells, such a wall should be transparent. What if we put 5 similar walls behind it, such that there were no straight lines going through all the walls? Would that be transparent to the spells? How does magic know what a “solid barrier” or a “hole” is, anyways?

Answer: spells try to squeeze and navigate around barriers while going to their target in a mostly straight line. Wherever a spell can squeeze past something depends on the size of the spell and the geometry of the environment, and relies on the same kind of general physics as any other squeezing of objects.

You need Line of Effect to cast a spell. Do casters know wherever they have this, or are they casting blind? If they know this, could you pair up with a buddy and sweep the environment for invisible enemies by checking where you do and don’t have line of effect to them (because it is blocked by an invisible enemy)? If they don’t know this, what happens if they try to cast without line of effect?

Answer: casters don’t naturally know wherever they have line of effect due to locality. They may have an easy way to check, however. If you cast without line of effect, then the spell would either splash against the intervening barrier, or affect it as normal.

Counterspelling requires you to see the enemy caster, ready an action, identify their spell, and cast a counterspell. What if you don’t identify their spell, but can guess at what they were casting anyways? What if you were reading their mind, and could know what they were casting that way? It doesn’t really make sense that you would need to make a spellcraft check in that case.

Answer: spellcraft check is only necessary to identify the spell. If you could guess the spell in some other form, you can counterspell. If you guess wrong, you waste a spell and no counterspell happens.

Do you need Line of Effect to counterspell?

You do need Line of Effect to their spell as it moves through the environment in order to counterspell, because your spell has to affect their spell, and in order for this to happen they have to touch.

What if instead of counterspelling, you were to throw up a big barrier in between the caster and the target. Would that interrupt their spell?

This would work. Spells move at a certain - large, but finite - speed. If a barrier showed up before the spell got there, it would interrupt the spell. Corollary: it should be possible, though immensely difficult, to interrupt spells with large shields.

As you can see, just by having some basic understanding of what spells are, we can already answer a broad range of edge case questions about spell mechanics. We even get some novel effects - such as that combination of force walls and dimensional lock blocks scrying - that fit perfectly into the overall picture. Next up, we’ll talk about my reductionist model of souls. Meanwhile, if you enjoy what I write, you can subscribe to receive updates by email:

I like the implications for counterspelling!