There are many games under the umbrella of Pen and Paper RPGs, but none are more widely known than Dungeons and Dragons. Indeed, this trademark is often used as a synonym for the genre as a whole, and this substitution is not without cause. Today I’d like to talk about one half of that label - the dungeons, a staple of Pen and Paper RPGs.

What is a dungeon? How do you design one? Most importantly, why are you bothering to do so? Knowing the answers to these questions is an essential part of being a good GM, and I hope to offer some clarity on this subject.

As usual, if you are confused about any terms, make sure to check out the glossary, and if you are looking for other posts, check out the blog map.

1. Definitions

Let’s start with the basics. What is a dungeon?

The way I think about it, “dungeon” is one of the building blocks of any kind of long-term PNP RPG play, be it a campaign or something else. And its purpose is to be a content package.

What does this mean? Your players will almost certainly have different utility functions; satisfying all of them every single second is going to be impossible. In order to satisfy everyone you will have to juggle priorities: one moment one person is enjoying the game to the fullest, another moment someone else, and so on. In general, there are infinitely many ways to mix and match different experiences in order to, on average, satisfy everyone at the table; however, some ways are much more convenient and controllable.

Think about this as a nutritious meal. Your body requires a certain amount of carbohydrates, proteins, vitamins and so on every day. In general, there are infinitely many ways to mix these elements into a meal, but in practice you will probably settle down on a dozen or so recipes that are the most convenient to make with the ingredients you have access to. In the same way, there are convenient methods to package PNP RPG content in ways that, on average, satisfy all your players. Dungeons are one of these methods, focused on the kind of fun that can be delivered by byte-sized, atomic experiences, also called challenges.

Obviously, “dungeon” is also a loose classification for locations in the world, based on wherever interactions of players with them will function as the aforementioned content package. Because of this “subjective” definition of a dungeon, there can’t be a strict line between “dungeon” and “not a dungeon”: in fact, the same physical place can fit the label in one session and not at all in the next, depending on what is happening there.

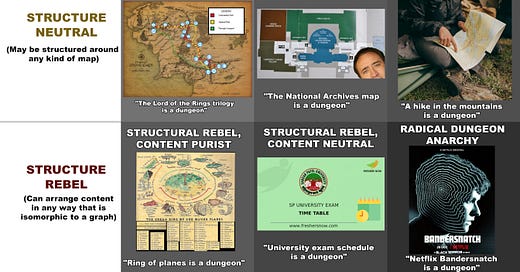

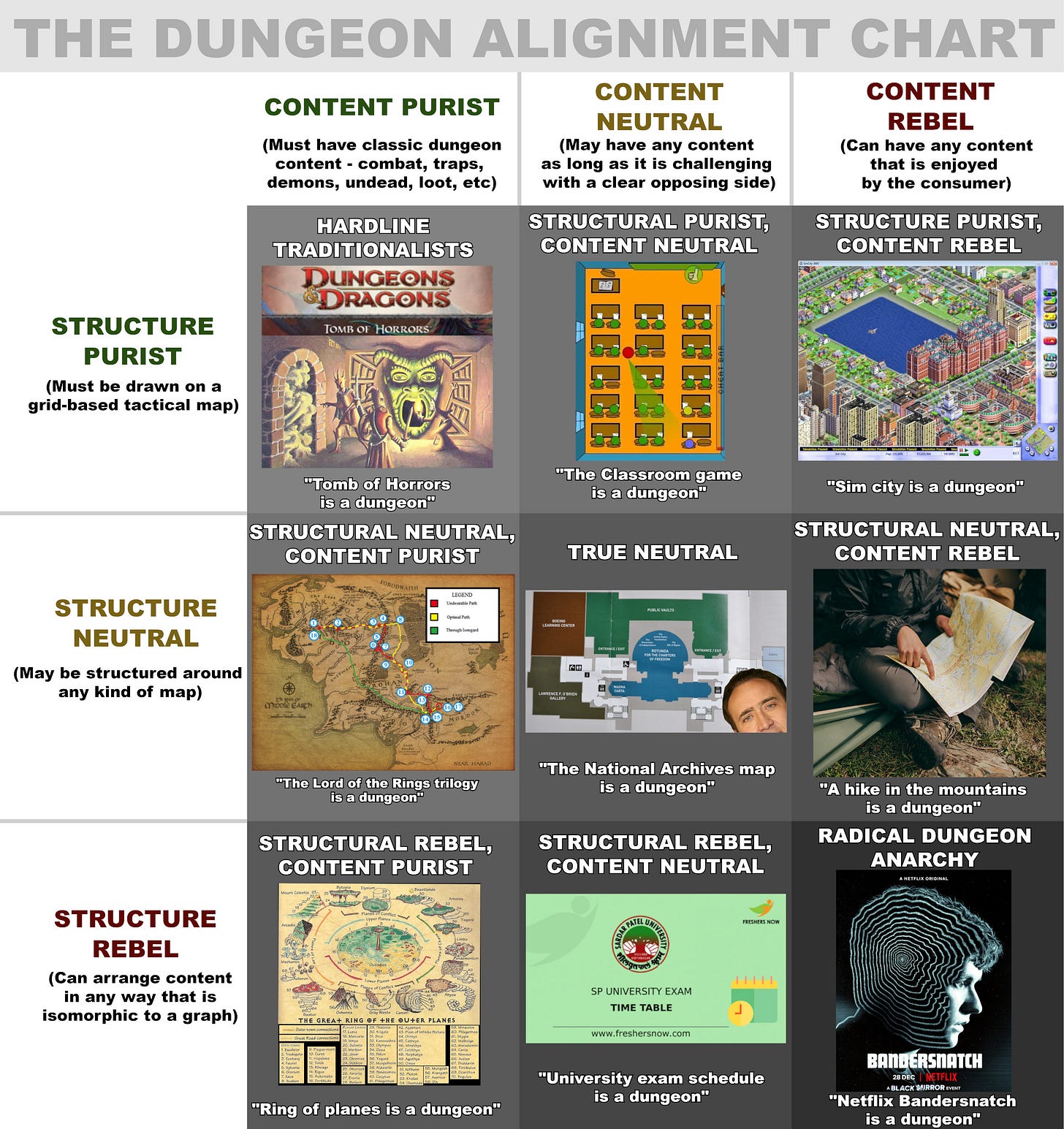

2. Classification

There are four core principles I use when thinking about dungeons as content packages. You may be able to find examples that don’t fit this classification at all yet still are rightfully dungeons, but I think they will be quite rare.

Disposable.

This is the first core feature - in terms of player engagement, dungeons are explicitly temporary. The party will come for a visit, they will do whatever it is they came to achieve, and then they will leave. In almost every scenario, they will not expect to ever come back.

Why is this important? Because of how this affects the design of the dungeon. If you know you will only need the location temporarily, you know you won’t need to design every single feature in excruciating detail: the players will never poke strongly enough at the edges of your creation to find the inconsistencies inherent in any quick draft. Furthermore, you are free to try unusual things: if they do not work out, the harm is only temporary.

In fact, you are almost forced to do something important or unusual with every dungeon you throw into your campaign. A location players will visit many times - a city hub, a home base, a well-known bar - can afford to be “ordinary”, as that will make acclimating to it easier. But if a dungeon feels ordinary, then your players may well just get bored after the second one.

Just like every other principle, this is not a hard rule. For example, imagine that players worked for a local baron for multiple sessions, getting used to his castle, going on various quests, and so on. Castle of the baron, naturally, is not a dungeon. But if players spontaneously decide to rob the baron, the castle becomes a dungeon for the duration of the heist.

Focus on several fast-paced challenges.

The second feature of a dungeon has to do with what’s in it. Specifically, there are challenges.

But not just any challenges. Dungeons focus on “atomic” challenges: the kind you can fit into a metaphorical room. An atomic challenge has to be solvable “on the spot”: you don’t generally have to leave and come back at a later time to take a crack at it. It is separable: its solution should be independent from solutions to other challenges within the same dungeon, or at best connect to them at specific well defined points. It is also relatively quick: if players spend two sessions on the same challenge, it’s not atomic. Generally, you are looking at something that takes from ten minutes to several hours to solve. This is why they fit into a “metaphorical room”: you can walk into one door, solve the challenge, and walk out the other.

Typical examples of atomic challenges are puzzles, combat, stealth sections, traps, and so on.

Some might say that this covers pretty much all challenges in a PNP RPG, so saying that a dungeon focuses on them says nothing of substance. This is naive: while atomic challenges are stereotypical examples of PNP RPG play, they are far from the only thing you would face at the table. For example, most campaigns can be seen as a long-form challenge: you have to find the Big Bad, figure out what their goal is, and defeat them. Similarly, smaller, logically connected parts of the campaign can involve challenges that would require players to leave for multiple sessions in order to find a solution: a lot of long-term subgoals take this form. If players talk to an NPC in order to make them a long-term ally, I would generally not consider this to fit the atomic label. Finally, if a challenge isn’t connected to a location, it isn’t made for a dungeon: more on this later.

Yes, atomic challenges will most likely be what takes 90% of the time in your game. However, the other 10% will be something else: something that dungeons don’t focus on.

Well-defined, mappable place.

Next essential feature of a dungeon is that it should be well-defined and mappable. Let’s start with well-defined.

A place being well-defined means that it has specific size and shape, known borders, and a static, “objective” geometry. For example, a building is well-defined: the walls are its borders, the geometry does not change on the spot, and the size is not subjective. Compare this to a location like “outskirts of town” or “deep forest”. Where do those begin or end? There is no intuitive border to settle on, and the estimated size would vary from person to person. It is hard to explore a place when you can’t even be sure if you are inside it.

This is further worsened by the simple fact that PNP RPGs are largely games of imagination, and human imagination is fickle and malleable. Furthermore, it is not shared between people. Any description you make over the course of the game is necessarily more vague than you intended it, because other people do not share your mental image of the place you are describing, and also because you yourself can not have a static mental image of anything. This means that if you are describing a vague location (deep forest), then you may as well tell the players they are floating in a sea of milky white, for all the connection they will have to the place. You will forget to describe essential features of the terrain, your players will forget what you described, you yourself will modify the image subconsciously just due to thinking about it for a bit, and what little you managed to convey would be hopelessly warped by the translation errors between your mental image, english, and the mental images inside your players’ heads.

The only hope at all there is in describing a consistent static place is to base your description on something that can’t change as easily as your thoughts: numbers, or lines on paper. If you know that the room you are describing is 20 meters long, it will not grow larger or smaller as your whims demand. It will stay in place. Better yet, if you draw it on paper then not only will it stay in place, the players will understand you perfectly, and they will also have something to orient themselves around.

This is what I mean by a dungeon being well-defined. On top of this, it should also be mappable.

This doesn’t just mean that it should be possible to put the dungeon on some kind of map. It means that it should be possible to put the dungeon on a map that is properly scaled to reflect player interests. For example, a city map reflects the geometry of the city, but it is far too large to reflect the interests of someone exploring a specific city block.

The detail of the map would differ from game to game, but in general, players should be able to have a pretty concrete idea about where they are in relation to every other relevant part of the dungeon or dungeon rooms, and how easily they can move around. Most importantly, the map has to be scaled to the atomic challenges the players would be facing. For example, I would not call a forest map which only contained some core locations as points connected by vague roads to be scaled well enough to be a dungeon, if the core challenges would involve tactical combat on separate, much more “zoomed in” maps. But if the core challenges have to do with something on the level of the forest (Maybe setting up some kind of large-scale ritual by drawing a ritual circle on the map), then this map can represent a “forest dungeon”.

The main idea behind making the dungeon mappable is to allow players to use their precise location in space as a core tool at their disposal when solving the challenges presented to them, as opposed to a vague and irrelevant consideration.

Room-by-room exploration.

Final feature of a dungeon is that it should be explorable chunk by chunk, room by room, door by door. This means two things: first, there should be something to explore. Second, this exploration should come in nice little chunks.

This is a brother feature to the focus on atomic challenges. While challenges focus on delivering tactical and puzzle-based fun, revealing the dungeon chunk by chunk deals with the exploration and novelty interests. Furthermore, it prevents the players from being overloaded with too much information: the larger their “circle of vision”, the more they have to take in at once, and thus the less they can focus on any particular feature.

Note that while the classical way to achieve this is to split the dungeon into literal rooms, this isn’t the only way to do it: any method that lets you meter out exploration in chunks should be fine.

3. Stereotypes

In my opinion, what is outlined above are all the essential properties of a dungeon. Everything else - no matter how closely it is associated with dungeons in PNP RPGs in public consciousness - is entirely secondary and absolutely optional. This includes:

Being located underground, in caves or stone basements.

In common parlance the word “dungeon” generally refers to a stone structure located underground, for example as a basement level to a castle. If you google “dungeons and dragons dungeon” you would likewise find lots of artwork showcasing these environments. It is therefore unsurprising that when someone talks about “dungeons”, their mind is automatically drawn to these stereotypical examples.

This is nothing more than a failure of imagination, and an unacceptable one if you are trying to be a great GM. Nothing about the actual purpose of a dungeon when it comes to running your game requires it to be underground. Open locations provide equally good opportunities for combat encounters, puzzles, and so on: you can take almost any dungeon and fairly easily convert it to take place on a flying platform high in the sky as opposed to underneath the ground.

That being said, the dungeon having strong solid walls does make it easier to separate challenges from one another, and deliver exploration in small chunks. But that is just one method of achieving this: there is no reason to confine yourself to it.

Having to do with burial sites/cult hideouts/dragon lairs/etc.

The thematics of the dungeon or it’s occupants are likewise not important. Yes, dungeons are stereotypically associated with these themes, and a lot of pre-written adventures include them. But this is mostly just a historical correlation: fighting through a castle filled with normal humans entirely disinterested in worshiping elder gods can likewise count as a dungeon.

Having treasure and loot.

This one is somewhat more questionable, but I think it’s important to separate the concerns here. Players get fun from finding loot, so including loot in the dungeon can deliver the type of byte-sized fun that I described above. However, it isn’t strictly necessary, and so it can’t be said to be a key feature of a dungeon.

There are two main ways to have a dungeon without any loot. First, you can front- or back- load the treasure: it can be an advance payment from some NPC to the players for clearing the dungeon, for example. Second, you can just skip the loot entirely, and focus on other types of fun, depending on your player group. If your players don’t enjoy digging through piles of loot for the good stuff, this may even be desirable.

Having monsters, especially any kind of boss.

Even monsters aren’t strictly necessary! Yes, they are one of the most stereotypical components of a dungeon, but in the end they are simply vehicles that deliver several distinct types of fun - mostly combat. If the challenges you picked for your dungeon do not include that type of fun, then there is no real need for monsters to exist.

At the end of the day, a dungeon is just a package. What you put into that package is window dressing, and would depend on the tastes of your players and yourself.

Now that I have established what I mean by a dungeon, the next post will deal with the question of how to design one, and wherever you should be doing it in the first place.

Meanwhile, if you enjoy what I write, you can subscribe to receive updates by email:

I like the idea of the above-ground dungeon, whether it's a castle or a series of buildings or something more exotic!